Ahead of the Afghan Presidential election, Impassion Afghanistan approached Small World News about creating a citizen journalism curriculum for delivery by radio. Given our previous experience in the country, particularly during the 2009 and 2010 elections, we were excited at the opportunity. The goal was simple, teach Afghan’s to participate in the Paiwandgah citizen journalism platform, by SMS and social media.

Paiwandgah, is “a social media and mobile-based platform for citizen journalism.” But in order to succeed, Impassion needed the assistance of someone with experience training journalists in difficult places. Small World News was a natural fit. However, rather than reinventing the wheel, and writing yet another journalism curriculum, we convinced Impassion director Eileen Guo to support adapting the StoryMaker curriculum for delivery via radio.

Some lessons didn’t yet exist, in particular content about physical safety and reporting techniques specific to documenting elections and political issues. In two short weeks John Smock and Brian Conley adapted the content, and Impassion Afghanistan had it translated into Dari, Pashto, and Uzbek. During the first round of the election, Paiwandgah received 525 reports from 27 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces.

We were really excited to be a part of this project, and look forward to what Paiwandgah will provide during the upcoming run-off election next month.

Check out digital recordings of the radio broadcasts on Soundcloud:

While most Americans spent this last weekend celebrating the Labor Day holiday, the world of media didn’t take a vacation. Here’s a couple of cool stories from around the internet that you won’t want to miss:

Building Media City-by-City

The US Embassy in Kabul reported on its Facebook page that the first of many USAID-funded Community Media Centers has opened in Herat, Afghanistan. These media centers provide tools and training in everything from basic computer use to advanced multimedia editing, and are open to the public, including local small business owners and civil society organizations.

From the post: Roqeya Ahmadi, a resident of Hirat, has already become a regular visitor to the center, coming for training in digital photography and videography. Multimedia is the cornerstone of society, especially in Afghanistan, she said. After three decades of war, its an effective way to increase our people’s knowledge and to expand their vision of what they can do with their lives.

The plan is currently to open at least three more centers in the coming weeks, in Mazar-i-Sharif, Jalalabad, and Kandahar, with the longterm goal of creating a nationwide network of community media centers.

These community centers are an excellent idea, and should greatly increase exposure of local citizens to the tools and training needed to make high quality, high impact media. Small World News has conducted trainings in conjunction with two of these media centers in Herat and Jalalabad, which you can read about here.

Do you have a media center in your neighborhood? While creating one in Afghanistan is a challenge to be sure, you might already have the tools and contacts to start your own right where you live. Talk to your friends who like to shoot photos, post videos, and write blogs, and see what you can organize right in your own community. Don’t forget to grab a copy of the Small World News Guide to Safely and Securely Producing Media to be sure you’re publishing the best media you possibly can.

Missing in Libya

Mafqood is a new venture by Tripoli’s infamous Free Generation Movement and others in Libya to crowdsource the job of locating persons who’ve gone missing over the course of the country’s civil war. The website allows users to provide a detailed description of the missing person, upload photos, and explain the circumstances surrounding their disappearance. The descriptions are combined into a database, currently numbering over 100 reports, although it is unclear at the moment who has access – authorized or otherwise – to this database, and how exactly each entry will be investigated.

Still, the project shows some exciting potential. Take this story from Alive in Libya about volunteers with the Red Crescent in Benghazi. They are doing roughly the same job as Mafqood, although their time is split both compiling reports of missing persons as well as carrying out the difficult task of actually investigating and tracking them down. It’s easy to see how crowdsourcing only one piece of the job – gathering reports – could offer a big gain in efficiency if properly integrated with existing humanitarian efforts, such as the Red Crescent’s mission of tracking the missing and disappeared.

Of further interest to us here at SWN would be combining the efforts of Mafqood with additional technology, particularly mapping tools such as Ushahidi, to allow better visualization and processing of the data, as well as mobile tools like Frontline SMS, which would allow citizens with only a mobile phone to submit reports of missing persons and use call-in tip lines for locating the disappeared.

Hey Man, Nice Shot

John Pollock has a fascinating article up at MIT’s Technology Review examining the resilience of new media technology, as told through the story of Libya’s most famous journalist Mohammed Nabous, who was killed by Gaddafi forces while reporting on March 19.

From the post: “When the revolution started, Gaddafi cut all means of communication outside Libya,” says Gihan Badi, a Libyan architect based in the UK. She calls [Mohammed Nabbous], who is one of her best friends, “this genius guy,” in part because he saw what needed to be done and reacted fast. He left the street protests to spend two days rigging up a satellite connection for live feeds. “He just took all these lies away; he was sending a clear message to the whole world.”

A lot of people were involved. Nabbous reached out into his own and other networks. A group of figures like Badi acted as critical nodes, linking expatriate Libyans and other supporters. A friend of Mo’s working for a German supplier of cellphones to Libya got together some equipment, which was brought from Germany and smuggled into Benghazi via Egypt.

Even as the Gaddafi regime scrambled to block all communication, the technology, and much more importantly, dedicated citizens on the ground, kept the lines of communication open, between Libya and the outside world, and between Libyans themselves. As we’ve seen repeatedly, in Libya as well as elsewhere like Egypt and Iran, social media is extremely difficult for authoritarian regimes to cut off, as the very features that make new media new also make it nearly impossible to stop. Put simply, you can block the internet, but you can’t stop the media; You can kill Mohammed Nabous, but you can’t stop citizen journalists from telling their stories.

But the obvious power of martyrdom narratives and resilient networks doesn’t mean that they’re without fault. Nabous himself was a vocal proponent of the Transitional National Council, calling into question his independence as a critical journalist.

A free press, the goal in Nabbous’ and many other Libyans’ mind, does not consist of merely the ability to produce media, but also the fundamental elements of critical, independent journalism. Social media creates a system that is more resilient than traditional media outlets, but it is also more open, and thus subject to abuse.

With the system as open as it is, how do you preserve the integrity of journalism? How do you prevent, say, the rebels from filibustering the open system with propaganda, or pro-regime elements from poisoning it with misinformation? These are not easy questions to answer, although it certainly begins with ensuring that the system is so open, so broadly inclusive of all segments of society (official, as with the TNC, or unofficial, as with opposition groups or unheard communities) that no voice is able to dominate or interfere with the others.

From the Ushahidi blog:

The Ushahidi community consists of a diverse group of people who have helped extend, translate and deploy the platform around the world. The Beta version in 2009 was translated into Spanish, even before Swahili. That early adoption and use lay the groundwork for even more adoption in Latin America, and with other deployment partners, we saw uses from India, Kenya, Afghanistan and many others. It is with gratitude that we recognize the organizations that help Ushahidi deploy projects by awarding the�Deployment Partner 2011�designation. What this means is that these organizations have shown that they are well versed in customizing the platform, engaging the community and deploying with a strategy that shows potential and informs others. We will be awarding these designations periodically as organizations continue to work with us.

We appreciate being named as one of their official partners, especially alongside some of the most impactful – and frankly coolest – crowdmapping projects out there (Citivox, Emoksha, Digital Democracy, just to name a few).

The impact of mapping reports is easy to recognize, and Ushahidi was one of those innovations in new media technology that really made us sit up and take notice. Our first exposure to it was Sharek961, in Lebanon, and we knew immediately that this was a powerful tool with the potential for huge impact.

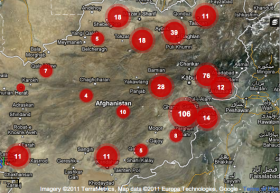

For one deployment, we partnered with the Free and Fair Election Foundation of Afghanistan (FEFA) to map their observation reports for the 2010 Wolesi Jurga elections. Observers around the country sent in their reports via SMS, which were then matched with the gps coordinates of their specific polling station. This alone gave us a startling new look at the same data they’ve been gathering in previous elections, but the real eye-opening moment came when they presented their findings at a press conference the day after the election.

For this press conference, FEFA displayed its Ushahidi map on a projector screen behind them as they announced their preliminary findings. Rather than enduring an all-too-familiar press event filled with statistics and obtuse data, the entire press contingent was transfixed with the maps. As the representatives spoke, the map onscreen changed to correspond with their reports – violence, tampering, intimidation. The journalists were constantly swiveling their heads to snap pictures and follow along with the map.

We appreciate all the support we’ve received along the way from the Ushahidi developers and their amazing community, and we’re glad to see such a great group of people continuing to succeed. We think their work is an important and indispensable tool to help journalists, as well as citizens themselves, to document and report news.

According to a recent San Francisco Chronicle article posted on SFGate.com:

The international aid agency Oxfam says USAID awards more than half of its Afghan aid to just five U.S. private contractors with close political ties in Washington: KBR, the Louis Berger Group, Bearing Point, DynCorp International and Chemonics International. USAID allows contractors to budget $500,000 annual salaries and benefits for high-ranking employees, and $200,000 for lower-ranking administrators, according to Rashid. All expatriate employees receive a bonus of up to 70 percent for hazard and hardship pay. The average Afghan civil servant, however, receives less than $1,000 a month.

Rashid and other critics say waste is built into the system. Expatriate employees bank most of their salary because companies pay for employee travel and living expenses.

Now, the cure for what some might call corruption or others, charitably, the misdirection of funds, is outside the purview of Small World News. However, later in the article, this brings something to mind:

Afghan officials and aid workers say smaller nongovernmental organizations that emphasize people-to-people aid have helped Afghan society and have kept overhead costs low. Former Finance Ministry adviser Rashid said Washington should rely more on such groups and Afghans themselves to administer future programs.

But Rashid concedes that direct funding of the Afghan government and contractors could also lead to increased corruption, a problem that has gained significant ground since the Taliban regime fell. But he says a multilayer system with improved oversight could diminish fraud.

As I wrote yesterday, we believe that an independent media network, staffed with local journalists, in collaboration with international direction, and an international focus, could make great steps toward improving the use of aid as well as an understanding of how Afghans really feel about subjects as disparate as US airstrikes, new roads, and the Karzai lead government. Without taking a stance on supporting local observation and accountability, we can’t reasonable expect to improve our relationship with the locals, can we?

Small World News proposes to build a local network and report on all manner of issues. We would be open to taking direction/requests on topics of coverage from development agencies and others, but we would expect independence. Only by valuing the work of locals, while keeping them honest and responsive, without the interference of other government interests, can we use technology to create a transparent and in-depth picture of the happenings all over Afghanistan.

Only by prioritizing the perspective of locals can we build honest and open dialogue toward increased international peace and stability. Only by learning who the Afghans are that we speak so much about, can we step back from the exoticizing and ridiculous obsession with “arming” or “bribing” the tribes. This has been tried many times, by Britain ni the 1800s, by the Soviets in the 80s, by the post-Soviet government in the 90s, and by the US in 2001-see Northern Alliance. Arming the tribes brings us to our current moment.

With a local network sourcing content and teaching the world about Afghanistan, collaborating with an international team building the platform and distributing content, as well as combining quantitative data to improve how we analyze the reporting, we can have a thoughtful, successful strategy for assisting Afghanistan with its current moment, and look forward.