by Jonathan Pednault

Squeezed between the sea and the walls of the old city, the Corinthia hotel once droned with swarms of squatting journalists and activists that anxiously awaited the capture of colonel Gaddafi, drinking pitch-dark Nescafés on tables coated with ashes and unwashed plates of half-eaten meals. Nowadays, the luxurious building has reverted to its old, regular clientele; businessmen, politicians and civil society moguls that quietly chat in the smoke-free lobby while drinking macchiatos. For some at least, life goes on in Tripoli. And for the journalist who remembers the city at the excitingly gullible peak of its post-liberation joy, the cold shower of unforgiving realism that has rained on Libya since two years now has one question the very notion of the freedom that was fought for.

Traveling as a journalist is poles apart from traveling as a journalist trainer. The questions, the energy and the mindsets are different. From researching the best ways to paint a given situation to teaching others to do so, one at times loses a sense of perspective of what exactly happens in the country to concentrate on the well-being and progression of the trainees. Political systems, social contexts and events become elements to deal with and experience rather than merely describe and analyze. In a place like Libya, no matter how short the stay, this means experiencing the doom and despair of the post-revolutionary state of affairs with and through the trainees instead of simply noticing it.

A hundred miles south of Tripoli stands the demolished city of Bani Walid, a former stronghold of Colonel Gaddafi. Amongst its rubbles lives one of our trainees, a short and nervous man from the Warfala tribe. Everyday, he’d make the two hours drive to the capital to attend the SWN workshop and undergo his university lectures. For him as for many others, the revolution, it seems, had not proved a great leap forward. With his house destroyed and his family less influential, he now had to keep silent his last name for fears of retribution from former rebels and revolutionaries, still keen on singling out families that had ties with the regime. He was, after all, but the distant nephew of some obscure Gaddafi official. Enough for a good beating by some katiba members, he feared. But his fear extended farther – except to the trainers, he would not tell his colleagues of his tribe’s name. Too afraid, he said.

Afraid: other trainees were too. Despite the powerful promise of free speech brought by the revolution, there remain some topics that in the eyes of many are best left unspoken and unseen. Such as the huge garbage dump that some thought wise to install right by the Mediterranean sea after the revolution. A coastal landfill site that one of SWN’s trainees – a tall and heavy black Libyan with little prior experience in journalistic production – found the guts to film, after much fear and much encouragement. And this, despite the place being the property of a family of former katiba members and friends of his, who were absolutely not keen on having him nose around. Venturing at dusk on the parcel of land, he came up the next morning with depressing images of trucks dumping tons of trash into the sea, garbage-burning fires and desolate landscapes.

An impressive piece of local journalistic work produced with StoryMaker, SWN’s trainee did what no foreign camera crew would have ever been able to emulate in such context. A strong testament, overall, to the StoryMaker application’s capacity to enable strong yet discrete production of multimedia content in a difficult media environment. In that regard, the StoryMaker training provided by SWN could hardly be more in touch with the realities faced by the many activists and journalists who operate in dictatorial or transitional political spaces such as Libya. Small and inconspicuous, the Androïd devices on which the application runs can easily be dissimulated. Easy to use and provided with a practical off-line curriculum, StoryMaker can be employed by anyone – with or with no prior shooting, editing or journalistic experience. Quite an advantage in places where users do not necessarily have a lot of existing computer or technical knowledge. And a cheap option for places where cellphones are already readily available and used.

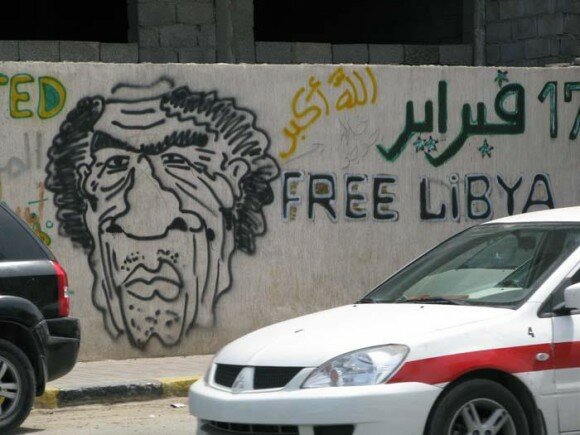

Two years later, the revolution has brought little to the Libyans if economic uncertainty, political instability and social discouragement and fear. The transitional waltzes, cadenced with intermezzos of AK-47, car-bombs and political assassinations, haven’t quite yet lived up to the Libyans’ dreams of democracy, freedom and economic growth. Their critics nowadays barely stop short from longing for the good old days. And the ardor of the revolutionary spirit that engulfed the determined youth has now left place to the unchallenging dictatorship of the «Inch’Allah» mentality. The actors and factors are so many anyway that one would have trouble finding any defined entity to rebel against. And so life goes on, indeed. A depressing one, for that matter.

But where hope seems slight, the few that keep on striving for the greater good often carry the secret ambitions of the many. Journalism trainings of the likes that SWN recently carried on in Tripoli are but a drop of water in front of the ocean of unpredictable predicaments that surrounds Libya. But independent and well-trained media professionals equipped with the latest tools provided by technology can, in this age of social networking, change the self-perception of a people and the course of a nation. Surely more than macchiato-drinking businessmen, politicians and civil society moguls, anyway.

Jonathan Pednault is a freelance journalist from Montreal, Canada. In the spring of 2013, he was an instructor for a mobile phone multimedia production workshop in Tripoli, Libya, using StoryMaker. It was his first experience working with SWN.