There are lots of reasons why mobile devices are replacing computers as the primary platform for social media and citizen journalism. Mobiles are portable. They can shoot photo and video. They are cheaper than computers.

In Afghanistan there are some additional advantages to mobiles. A computer will get the attention of Taliban at a checkpoint. It suggests work with government or with Western NGOs. But phones have become so ubiquitous they go unnoticed.

This anecdote underscores the reality here: following the national election earlier this year the potential for citizen journalists using mobile tools to continue to make an impact is great, but the challenges remain substantial.

John Smock 2014

As part of the second Afghan Social Media Summit in October, Small World News provided a four-day training of trainers (ToT) workshop in Kabul. The 15 participants came from 10 provinces. Some were teachers, some students and some journalists or community advocates. All were enthusiastic about the opportunity to take the material presented back to their home province for use in workshops of their own.

The workshops were held at the office training space of Impassion Afghanistan, the organization that organized the ASMS summit. We covered training techniques on material as basic as how a web browser work to topics as advanced digital security and how to build audience around community issues using hashtags. Participants quickly built relationships with one another – and a Facebook group – that will allow them to continue to exchange ideas and resources after they return home.

John Smock 2014

Illiteracy rate in many provinces remain high in Afghanistan and dependable Internet and smart phone use low. Yet Facebook and WhatsApp are widely used, mostly among younger Afghans. During the election Small World News helped develop the curriculum for several election-related projects, including an SMS/IVR reporting project and another to encourage community peace reporting and solutions journalism. Several of the participants in the ToT workshops were part of these earlier projects.

In January of 2015 the United Nations will formally end the ISAF mission. President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Officer Abdullah Abdullah have committed to a variety of good governance programs for Afghanistan. The nation could be heading toward a long-awaited era of peace and development.

John Smock 2014

There is no doubt the citizen journalists working with mobile tools in provinces across the country will play a growing role in monitoring how both local and national government deliver on the opportunity.

Small World News is excited to announce that we are designing a yet to be named android app. The app will support citizen journalists and professionals alike in the production of multimedia news packages.

Specifically, this open source app enables existing and aspiring journalists all over the world to produce and publish professional-grade news with their Android phone, as safely and securely as possible. It provides an interactive training guide, walkthroughs, and templates for users to follow as they plan their piece and capture media. The app then helps assemble the content into a finished format, with cuts and basic graphics.

Our long time colleagues at the Guardian Project will be handling the development work for the app. They’re one of the best android development organizations out there and we should know. We’ve been testing out their amazing suite of applications for a few years now.

Poor digital and mobile security are an increasing threat to journalists and their sources. Partnering with the Guardian Project, will enable us to produce an app that considers the needs of media producers and sources over the entire journalistic process.

Initially, this work is being sponsored by two organizations, Radio Free Asia and Free Press Unlimited.

Radio Free Asia is a private, nonprofit corporation that broadcasts news and information in nine native Asian languages to listeners who do not have access to full and free news media. The purpose of RFA is to provide a forum for a variety of opinions and voices from within these Asian countries.

Free Press Unlimited is a Dutch media development NGO active in over forty countries, focusing on strengthening the capacity of local media professionals and media organizations.

This app will help improve the quality of mobile reporting, while ensuring a more safe and secure model of connecting creators with their audience than currently exists. We’re thrilled to be envisioning what’s next for mobile journalism. We will be blogging our work as we complete different parts, and we’ll be inviting beta testers to get involved later in the fall. So follow along our blog if you’d like a chance to be included in the early tests.

Steve Wyshywaniuk

One week ago, today, two video journalists from the city of Misurata were kidnapped while covering Libya’s historic national elections. I had the pleasure to meet and work with these men during my recent trip there with my colleague and co-trainer Louis Abelman in May 2012.

Abdelqadr Fassouk and Yusuf Badi worked together as part of a three man team during our video boot camp in Misurata. Together they worked to produce a story about the head of the nursing department at Misurata’s only hospital.

The team did great visual work at the time, demonstrating a clear understanding of how to produce brief news packages. However they missed one small detail. They decided to record the video without audio.

When Louis and I explained their mistake, Abdelqadr and Yusuf insisted on reshooting the piece in its entirety. They exemplified a typical character of Misuratis, willingness to do whatever it took to get the job done.

Though the two men work well as a team, it’s clear sometimes they face some tension. Abdelqadr wished to learn the basics of editing. He wanted to finish the piece quickly and submit it to the election awareness campaign SWN was working on with the support of Doha Centre for Media Freedom. Yusuf, on the other hand, was far more interested in cutting and re-cutting the piece. His goal was not to finish the piece, but to understand the editing software, deleting the finished sequence and starting from scratch each time.

The term “Frenemies” might be fitting. Both men were generally good humored and if they aren’t getting in each other’s way, I trust they’d have no better companion in such a trying time.

Despite their good company, I am greatly concerned about their safety. The Facebook era has meant that repeated false claims of their release have been widely distributed by colleagues, friends, and fellow Libyans who desperately want the news to be true. As of this writing, Abdelqadr and Yusuf are still detained, and though their general whereabouts are believed to be inside Bani Walid, their specific location is unknown.

Misurata and Bani Walid have a longstanding feud, exacerbated by the Libyan revolution. The kidnapping of two much-loved journalists from Misurata has pushed the conflict again to the front of discourse about the future of the new Libyan state. So far, Facebook rumors notwithstanding, negotiations have not yet completely broken down. Though many are campaigning to use the kidnapping as a pretext to return to war, they’ve thus far not been successful. For the sake of Abdelqadr, Yusuf, and all of Libya, I hope our friends will be freed without further violence.

Brian Conley

Small World News

[For additional information about Abdelqadr Fassouk and Yusuf Badi, see the Committee to Protect Journalists’s Libya alerts, Reporters Without Borders, and articles by the Libya Herald, Associated Press, and McClatchy.]

Small World News is in Libya for the third time since the revolution began. Although the revolutionary edge of the nation’s enthusiasm may have subsided, the enthusiasm itself has not. Libyans are excited to build their country, and actively looking for partners to provide assistance and mentorship. This desire led directly to the creation of our new project, a series of production bootcamps around the country. Throughout May, Louis Abelman and Brian Conley, along with Alive in Libya’s Mohamed M Essul will run a series of workshops across Libya.

We are excited by the broad support we have received from the Doha Centre for Media Freedom. With their support Small World News has developed a program that looks beyond training. We are using the phrase “production bootcamp” because we see each event as more than “training.” Our goal is to work side-by-side with Libyans across the country to produce a series of videos. These videos will form a campaign over the next several weeks encouraging Libyans to vote.

There is a general lack of capacity in the Libyan media to produce short, dynamic news packages quickly. Libyan news currently focuses primarily on talk shows, and studio-based news programming. By encouraging a bootcamp, on-the-job style experience, trainees will learn theory that is quickly informed by practice.

Currently there is also a huge lack of real information about the election. The day before registration began on May 1, many Libyans did not even know where to register. Others were confused about the exact purpose of registration. Furthermore, many Libyans are even unclear about when the elections should occur. Its June 19th according to our latest information, yet many still believe it is June 23rd.

The workshops will bring together a diverse group of media makers in each city. These trainees will work together in a series of production teams, conceiving a story, shooting the story, and finally assembling, all in a matter of days. We have crafted the campaign around the idea that individual Libyans are best suited to convince their fellow citizens to vote. We are attempting to blend short documentary features, telling one individual story, with energetic, get-out-the-vote style language. We hope this innovative approach will connect with average Libyans and educate them about the upcoming election.

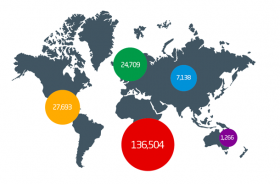

Our partners and colleagues over at the Engine Room are dedicated to organizing the best practices and experiences in the world of tech development. Taking what they find and openly sharing it for all of our benefit. This is why it’s important for all of us to take their social tech census.

By pooling our knowledge together we can all benefit by seeing what has worked for us in different locations, and help avoid making the same mistakes over and over. It’s important that we take the time to step back and communicate with our peers on the work we’re all dedicated to.

Here at Small World News we’re looking forward to seeing the results, so be sure to add your voice to the census today.

This week we released our latest guide. The new guide is an attempt to assist those who are forced to rely on satellite phones for communication, particularly in conflict areas and repressive states. Satellite phones are all closed source technology, making them an incredibly risky tool to rely on in life threatening situations.

Because satellite phones, or satphones, are an insecure tool, the first thing that must be said about this guide, is that this guide will not keep you safe and secure, but we believe it can keep you safer.

In the wake of the murder of two journalists in Homs last month, we published this guide as quickly as possible. It was originally developed to assist satphone users, particularly those working as activists and likely under severe threat from their government. It is not a complete guide for journalists, aid workers, or other use cases, though we believe it is a very good start.

Some individuals have already asked us about the risks of satellite modems.I Although this guide focuses on satphones, satellite modems share similar risks. The number one issue to remember is that it is very easy to locate your position via the radio transmission from your satellite broadcast. Whether you are using a phone, a modem, or a satellite pager, your transmissions are the first risk you take.

Please check out the guide, offer suggestions, and if we can assist you with better understanding the safety and security concerns around your technology and communications, let us know!

This week we’ve been looking at the different tools and tech being used by the local affiliate of the Occupy Together or Occupy Wall Street movement, also known as “We are the 99%.” Steve and Josh wrote about their experience at the protest, Josh investigating the opportunity posed by livestreaming, while Steve took some time to talk to some of the local media makers themselves.

I didn’t make it to the event, so instead of talking about experience at the protest last week, I’d like to discuss what can be gleaned from reviewing the media made by members of the occupy movement, and how Occupy Together might improve their impact by improving their media.

The bulk of Occupy Together media has focused on livestreaming. There are a few obvious reasons for this, its immediacy and ease due to readily available connectivity across a multitude of smartphones being perhaps the most obvious. I learned another reason today during a conversation with a friend and longtime media activist who has been heavily involved with the streaming and mobile broadcast efforts.

Because events are being broadcast in realtime by the participants, individuals with an interest in the continuance of their message, as well as the safety of the camp, livestreaming provides a potential deterrent to camp eviction. Police departments across the country are having to think twice about removing Occupy camps by force, a deterrent not historically available to disenfranchised groups occupying public space illegally, such as Portland’s homeless community.

Its clear how such a technique could be far more effective than previous attempts to monitor police violence at protests with offline cameras, that have media which must be copied and published at a later time. Now that individuals previously involved with the transitory summit-hopping actions of the global justice movement are partnering with newcomers to activism, its important to rethink the use of media as well as the effectiveness of other tactics.

While occupying physical space, and building a local power base provides a feeling of continuity and a space to begin organizing for change, its important to recognize he impact such a new organization has on existing issues. Occupy media has primarily focused so far on the actual Occupy events themselves, even things such as the We are the 99 Percent tumblr are activities focused in self-selection, individuals are choosing to participate.

Because of this dynamic, and the general focus of the mainstream media, Occupy is in danger of becoming more of a spectacle and a headline grabber, in the way the Tea Party has become. In order to create real, durable change, Occupiers need to tell the country and the international community what the media aren’t. They need to document the images of the real life 99%.

What if, in combination with documenting the events of the Occupy Portland encampment, some individuals took it upon themselves to start documenting the real and present issues of the 99% around Portland? This is whats necessary to provide context for the Occupy movement. Stories of today at the encampment provide a look at who the Occupiers are, and how the State is relating to them. However, it will take pointing the cameras outward, stepping out of protest comfort zones, and making an effort to explore the stories that are not yet being told if we want to know who the 99% really are.

//Photo via Streetcar Press’ Photostream

With the growing momentum behind the Occupy Wall Street movement, I knew there would be a lot of press at the Occupy Portland march. Josh and I went over and watched as they kicked off their march to speak to the media who associated themselves with the movement, see what tools they were using, and if there were any tricks I might be able to learn from them as well.

A lot of dSLRs were there, it’s clear that shooting dSLR is the approach that most excites people. There were a number of high quality audio recorders too. Speaking to people it’s clear that these high bench marks are simply what they expect of themselves. There were a number of other cameras, standard def mini Dv, even a High 8 camera that I recognized from my high school days. But, the majority of the movement was using dSLR cameras.

The number of cell phone pictures taken was pretty startling too. Almost anyone the march passed would take a picture of it. To post on Facebook, twitter, or to show their friends later at the bar is for them to say. But I lost track of counting cell phones photos being taken after seeing 40 and we had only gone two blocks.

One particular interesting setup was the few people who combined the sophistication of high quality cameras with cellular modem technology. Here is one person who was streaming video live via a LiveU backpack.

Here is another, a kit setup by Dan Kaufman (of crank my chain!), using the same method of cellular modem transmission, but with a homebrew approach.

This brought me back to the use of TXTmob at the 2004 RNC. It was not common yet to use text messages for widespread but specific communication, but protestors were utilizing it to keep each other informed. Now tools like twitter are indispensable to journalists and activists for monitoring breaking news as well as communicating with each other.

I see these early adopters as an example of what we have to expect. Right now cell phone technology is the easiest way to do this. You can affordably communicate with the world instantly. But, the more technologies like EyeFi cards and cell phone modems become cheaper and more affordable, the easier it will be to be step around the quality limitations of our every shrinking cell phones and utilize more powerful tools for story telling.

If you’re still interested, you can check out a few unedited interviews on our YouTube Page too:

Since launching in March, our journalists operating in Ajdabiya, Benghazi, and Misrata have produced 175 videos covering the revolution, the civil war, and the daily life of Libyan citizens. With the fall of the Gaddafi regime in Tripoli, Alive in Libya has now expanded to the capital, along with a new bureau in Zintan.

Training in Tripoli

Last weekend Alive in Libya, led by our Benghazi bureau chief Seraj Elalem, completed its first training session in Tripoli. 10 aspiring journalists, 5 women and 5 men, graduated from our course, and 4 of them signed on as contributors to Alive in Libya. More trainings will follow in the coming weeks as we continue to expand into previously inaccessible areas. You can see a selection of the new content from our Tripoli bureau by visiting the website.

New Site

The first thing you’ll notice when visiting the site is the new design. We’ve revamped the look and feel of the website to better complement the tremendous video content coming out of Libya. We’re interested in your feedback on the site, so please let us know what you think.

The next thing you’ll notice is the stark improvement in the skills of our reporters. As the trainings continue and our reporters gain experience and grow more comfortable, they push the boundaries of Libya’s new free press. We are encouraging our bureaus to innovate, and they have responded with useful techniques like English narration (which their Western audience surely appreciates) as well as more probing and critical reports in the wake of the revolution.

Support the Team

Alive in Libya still needs your help.

Our team is currently expanding into other cities in Libya, and your support will allow them to both train more journalists and ensure these journalists are properly equipped with cameras, microphones, and other tools. Your support will be instrumental in the establishment and future success of new Alive in Libya bureaus.

If you can help, please click here to support our team.

Yesterday my colleague Steve Wyshywaniuk addressed how Citizen Media might assist Egyptians and the international community to bear witness to the upcoming election in Egypt. If the current ban preventing international observers continues, Egyptian citizens will be the only ones with the potential to ensure the validity of the election. After thirty years under Hosni Mubarak, and a sum total of 57 years of totalitarian rule, Egyptians can hardly be expected to ensure a transparent, accurate election.

Despite these limitations, its certainly possible Egyptians can follow the example of other organizations attempting to ensure democratic elections through citizen observation, from Lebanon to Afghanistan, and as Josh Mull mentioned earlier this week, they already have some experience.

I founded Small World News with Steve Wyshywaniuk based on the assumption that, while technology is increasing the accessibility of the tools of democracy, that access is so far primarily limited to developed nations and the wealthiest citizens of lesser developed nations. There are simple tools such as OpenDataKit to create mobile-based election monitoring forms, or even more simply, using simple SMS forms to rapidly send in election updates from monitors in the field.

However, these tools and techniques are only accessible where they are known to local citizens and monitoring organizations. Other tools, such as digital cameras that are now so affordable as to be practically disposable still cost a large percentage of a citizens income in Egypt or many other countries. Even where affordable cameras exist, too often citizen journalists lack the knowledge of basic production techniques to improve the impact of their firsthand access to urgent events.

-Brian Conley, Co-Founder

//photo by Al-Ahram

At SWN HQ we’ve been discussing creative ways Egypt might be able to ensure their upcoming elections are free and fair. At this point the love affair between the Egyptian people and the Web last spring is painstakingly documented. But the recent announcement that the military council will maintain the emergency law into next year, shows that they need to commit to a long term relationship. The rumored dates for the upcoming election are November 21st, which would mean this critical election would take place under the same atmosphere as they did under Mubarak.

Citizen media was crucial to kicking off Egypt’s revolution, and it will be essential for monitoring each step it takes. Election monitoring technology is available that can allow citizens to collect reports about problems via SMS, media will need to be more sophisticated, and information will need to be more clearly sourced.

Just as I hope the media campaigns step up in quality, it is likely that the reaction to citizens uploading video, posting tweets, and communicating over facebook will be more sophisticated too. Just as Libya has learned from Egypt, Egypt will learn from everything in the last year.

Written by: Steve Wyshywaniuk ~ Co-Founder

//photo credit: Patrick Baz/AFP/Getty Images

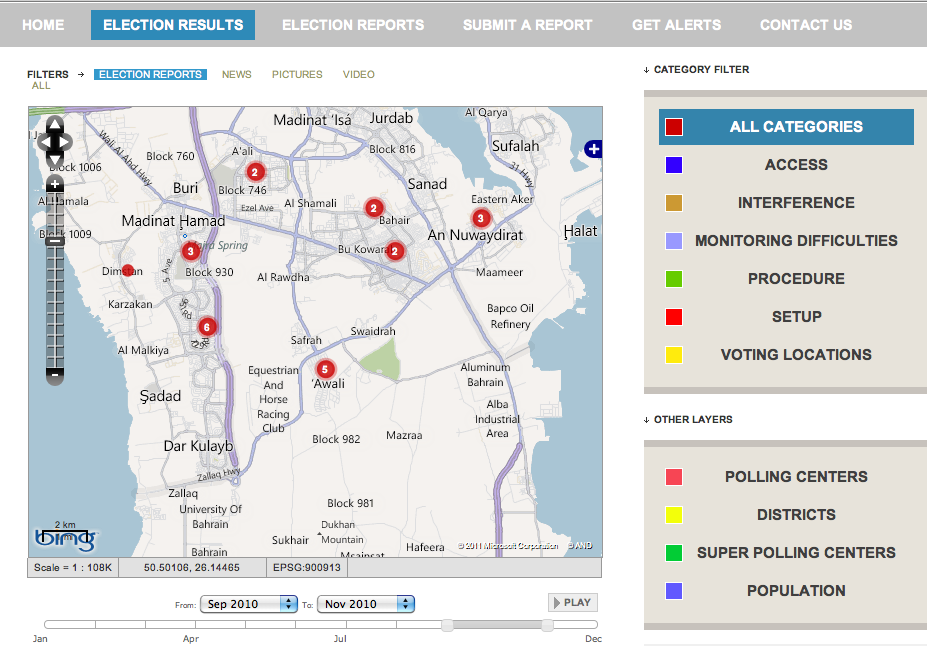

Yesterday in this space we discussed the upcoming elections in Egypt, and the need for international observers to work alongside local organizations to ensure the fairness and accuracy of the polls. International and local observers working together would allow reports of fraud, intimidation, and other improprieties to be more easily verified, increasing the legitimacy of the observation mission.

But what if Egypt’s military continues with its ban on foreign observers, and the burden of monitoring these critical and momentous elections is placed entirely on Egyptian citizens? What are some of the ways the observation mission can be empowered and bolstered without the presence of international monitors?

There are several examples of where election monitoring can be conducted in less than ideal circumstances, be it in police states with no access to foreign observers or in conflict zones with very little infrastructure and media access. Here are a few:

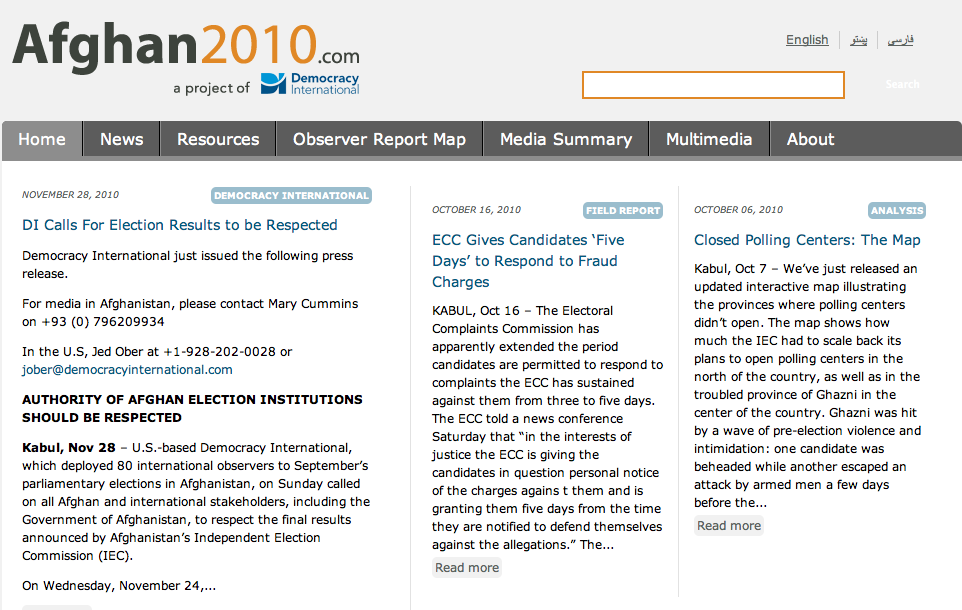

Afghan2010

Map Muraqeb

FEFA 2010

Monitoring elections is an incredibly complex and difficult task, particularly in this case with the crucial and unprecedented post-revolutionary elections in Egypt.

What are some of the other ways both the international community and Egyptian citizens can work to ensure a free and fair election? We will continue to monitor this story closely, and your suggestions, comments, and solutions are welcomed.

//Photo by Bikyamasr.com

Somali refugees in Kenya lack basic access to communication and information about the aid and services available to them. From Internews:

The assessment surveyed over 600 refugees and shows that large numbers of displaced Somalis don’t have the information they need to access basic aid: More than 70 percent of newly-arrived refugees say they lack information on how to register for aid and similar numbers say they need information on how to locate missing family members. High figures are also recorded for lack of information on how to access health care how to access shelter, how to communicate with family outside the camps and more.

The report suggests a number of excellent solutions:

The report makes several recommendations, including: conducting workshops on communications for humanitarian organizations; establishing a humanitarian communications officer in Dadaab for communicating with affected populations; increasing support to Star FM, the main Kenyan broadcaster in Somali language, for broadcasting local humanitarian information; and establishing a communications research hub and a media training center for both host and refugee communities. It is important to note that the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has already set up an Information Dissemination Group to specifically look into the communications needs of local communities “in the light of the current emergency and identified gaps by Internews’ assessment†(page 11).

What are some of the other ways that communication and access to information can be increased within the Dadaab camps?

Generally when media makers theorize on hyperlocal content, they consider it only in the context of developed communities with ready access to communication infrastructure (internet, television, etc). Further it is usually considered only as a complement to wider-scope media (such as the pairing of local news with nightly national news in the United States).

But the camp in Dadaab provides an especially difficult case, with its lack of access to most IT infrastructure (meaning no Facebook, no crowdmapping), and its need for exclusively local content (no need for international media organizations). The solutions that might immediately come to mind are almost certainly unworkable here.

Instead what is required is a concentrated effort on building the capacity of locals inside the camp to communicate and access information themselves. With this in mind, we can judge the recommendations of Internews’ report to be very much on the right track.

Expanding existing media systems, such as their example of StarFM, and developing the capacity of community leaders, as shown in the video, to provide their constituency with the necessary information will help move toward a realistic solution within the constraints of life in the refugee camp.

What else can be done? And what lessons – on hyperlocal media, on community information and communication, and on development, can be learned from the case of Dadaab?