There are lots of reasons why mobile devices are replacing computers as the primary platform for social media and citizen journalism. Mobiles are portable. They can shoot photo and video. They are cheaper than computers.

In Afghanistan there are some additional advantages to mobiles. A computer will get the attention of Taliban at a checkpoint. It suggests work with government or with Western NGOs. But phones have become so ubiquitous they go unnoticed.

This anecdote underscores the reality here: following the national election earlier this year the potential for citizen journalists using mobile tools to continue to make an impact is great, but the challenges remain substantial.

John Smock 2014

As part of the second Afghan Social Media Summit in October, Small World News provided a four-day training of trainers (ToT) workshop in Kabul. The 15 participants came from 10 provinces. Some were teachers, some students and some journalists or community advocates. All were enthusiastic about the opportunity to take the material presented back to their home province for use in workshops of their own.

The workshops were held at the office training space of Impassion Afghanistan, the organization that organized the ASMS summit. We covered training techniques on material as basic as how a web browser work to topics as advanced digital security and how to build audience around community issues using hashtags. Participants quickly built relationships with one another – and a Facebook group – that will allow them to continue to exchange ideas and resources after they return home.

John Smock 2014

Illiteracy rate in many provinces remain high in Afghanistan and dependable Internet and smart phone use low. Yet Facebook and WhatsApp are widely used, mostly among younger Afghans. During the election Small World News helped develop the curriculum for several election-related projects, including an SMS/IVR reporting project and another to encourage community peace reporting and solutions journalism. Several of the participants in the ToT workshops were part of these earlier projects.

In January of 2015 the United Nations will formally end the ISAF mission. President Ashraf Ghani and Chief Executive Officer Abdullah Abdullah have committed to a variety of good governance programs for Afghanistan. The nation could be heading toward a long-awaited era of peace and development.

John Smock 2014

There is no doubt the citizen journalists working with mobile tools in provinces across the country will play a growing role in monitoring how both local and national government deliver on the opportunity.

When floods gripped the Balkans, Radio Slobodna realized the agency needed a new approach to effectively cover the events. Several reporters lost their recording equipment. Where this wasn’t the case, the tools of radio reporting were just not enough to completely tell the story. Radio could impart how citizens felt, but lacked the kind of visceral impact possible with visual documentation of such devastation.

Radio Slobodna is the Bosnian affiliate of Radio Free Europe in the Balkans. In June the Prague Freedom Foundation, an independent foundation supporting indepedent media in eastern Europe, asked Small World News and StoryMaker to help reinvigorate Radio Slobodna. SWN worked with Radio Free Europe’s local partner in Sarajevo, providing new equipment and training in multimedia reporting with mobile devices. As the name suggests, Radio Slobodna is primarily a radio agency, but increasingly looks to the internet as a primary distribution point.

The agency produces a daily morning radio program and weekly television program. Thus far distribution via the internet is a secondary consideration. Historically reporters in the field have primarily filed audio dispatches and called in reports. A core team of staff reporters, based in Sarajevo, were responsible for all photo and video content. However, this structure is no longer tenable, increasingly, news agencies must ensure all staff are capable of capturing and reporting news in a variety of mediums, at any time.

With the support of the Prague Freedom Foundation, I traveled to Sarajevo, and delivered 25 android tablets running StoryMaker. Over two one-day workshops reporters with a variety of experience learned the basics of multimedia production with mobile devices and the StoryMaker app, which is now available in nine languages.

Providing Radio Slobodna’s staff Android tablets combined with the StoryMaker journalism app will help them stay ahead of the curve. This combined with an introduction to Small World News’ revolutionary social-first news strategy means Radio Slobodna’s journalists will be ready for whatever the next news cycle brings.

The reporters of Radio Slobodna produced a variety of short video projects during the workshop, including stories about the increasing rehabilitation of Tito’s legacy amongst Bosnians, the only woman copper worker in Sarajevo, and the renovation of the historic hotel Zagreb in downtown.

For reporters with access to professional photography and video equipment, as well as post-production software, StoryMaker provides an interesting addition to their kit. Rather than replacing this equipment, StoryMaker and mobile multimedia production should be seen as an accompaniment. With a mobile device and StoryMaker, journalists can quickly assemble and publish a rough cut of their story, directly from the scene.

StoryMaker will help Radio Slobodna increase the depth and variability of its coverage without investing huge sums in new equipment and training. Just following the workshop, staff reporter Ivana Bilic traveled to Topcic to document the reconstruction. Using StoryMaker she was able to quickly and effectively document the impact of the floods and the state of reconstruction. Check out the video below:

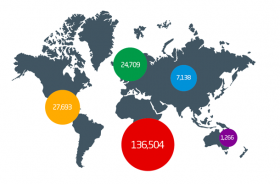

Ahead of the Afghan Presidential election, Impassion Afghanistan approached Small World News about creating a citizen journalism curriculum for delivery by radio. Given our previous experience in the country, particularly during the 2009 and 2010 elections, we were excited at the opportunity. The goal was simple, teach Afghan’s to participate in the Paiwandgah citizen journalism platform, by SMS and social media.

Paiwandgah, is “a social media and mobile-based platform for citizen journalism.” But in order to succeed, Impassion needed the assistance of someone with experience training journalists in difficult places. Small World News was a natural fit. However, rather than reinventing the wheel, and writing yet another journalism curriculum, we convinced Impassion director Eileen Guo to support adapting the StoryMaker curriculum for delivery via radio.

Some lessons didn’t yet exist, in particular content about physical safety and reporting techniques specific to documenting elections and political issues. In two short weeks John Smock and Brian Conley adapted the content, and Impassion Afghanistan had it translated into Dari, Pashto, and Uzbek. During the first round of the election, Paiwandgah received 525 reports from 27 of Afghanistan’s 34 provinces.

We were really excited to be a part of this project, and look forward to what Paiwandgah will provide during the upcoming run-off election next month.

Check out digital recordings of the radio broadcasts on Soundcloud:

When crises strike, the United Nations Office of Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), is consistently among the first institutions to intervene.. On the scene when violence recently re-ignited in the Central African Republic and immediately responsive to devastation caused by the 2012 typhoon that struck Tacloban in the Philippines, OCHA field officers are among few responding organizations with access to areas affected by crisis. By partnering with Small World News and implementing their StoryMaker app, OCHA field staff leverage their unique access to a world the general public does not know by creating compelling stories no one else is telling and share them with the world. And they can do all of this, needing nothing more than a smartphone.

Recognizing the importance of telling the story of their work from the field, OCHA’s communications office asked Small World News to provide training and mentoring to their Press Information Officers with the objective of empowering them to tell insightful stories from some of the most vulnerable places in the world. An all-in-one solution to creating and publishing stories, StoryMaker users focus on telling and sharing a compelling story with integrated guides, without being hampered by technical issues. Simple to learn and navigate, StoryMaker scales external communications objectives while supporting the generation of professional deliverables.

The March 2014 program launch transpired in Jordan and included twenty-seven OCHA field officers as well as their headquarters communications team. Equipped with varying degrees of experience in communications and public relations, trainees participated in an accelerated Small World News course in visual storytelling with a smartphone and the StoryMaker app. Despite the unusually brief convening for Phase One of this curriculum, trainees personally experienced great success in both learning the introductory curriculum and realizing the potential of this tool. Actively using StoryMaker throughout the program, trainees recognized diversity amongst their peers as they individually produced stories. These exercises aided in building camaraderie, compassion, and trust among participants allowing them to experience first-hand what information sharing can deliver for a large population of readers.

The trainees worked hard and came up with a fascinating array of interesting stories, from silly to saddening. While the approach varied greatly amongst participants, a number of themes were dominant, reflecting the similarities across much of UNOCHA’s work, despite offices and projects spanning the globe. Three stories, in particular, stood out.

In one case, two participants produced a story focusing on the impact of unemployment and interviewed a man working at the hotel as a chef. It was discovered that he had earned a master’s degree in computer science. Although there is a lack of jobs in that field, he found work as a chef at the hotel and doubles up by providing the IT support to the hotel.

Another group addressed the issue of orphans who have lost family due to tragedy. They made a humorous piece profiling three young cats the hotel has taken an affinity with. Their story profiled the cats struggle to find a place to live, in the face of opposition from hotel guests leading to their displacement.

Finally, the third group, who produced the best overall piece, was a fictional look at a woman displaced by a natural disaster. Although each of the individuals in the piece was acting, the combination of script and well-constructed visuals resulted in the creation of a story that provided each trainee a strong example of what they should try to produce during Phase Two of our program.

As Phase Two begins, Small World News will work closely with program trainees, OCHA field officers, back at their offices across the world. The continued curriculum includes Small World News advising them on choosing shots, interviewing ideal individuals, and coaching them through any technical difficulties they encounter. Sustained collaboration and mentoring will enrich their confidence in using StoryMaker and ensure overall program success for both OCHA and Small World News.

Small World News is looking forward to nurturing a relationship with OCHA. Sharing stories from refugees and people displaced by natural disasters and conflict will put a human face on some of the worst crises affecting the world today.

Please stay tuned for updates including additional outcomes of this program as their stories come in!

I spend a lot of time thinking about how to tell stories better. Everyday emerging technology is altering the way we think of storytelling. Storytelling choices and methods should be rooted in a clear understanding of your goals and specific needs. These goals must also be tempered by your available resources. Finally you want to consider how your audience’s expectations also serve to mold your strategy.

For example, while more people join Twitter everyday, there are still many communities not represented there. When I was working in Libya in 2011, we started a hashtag #AskaLibyan to promote engagement between the international community and Libyan citizens. At the time internet connectivity was virtually nonexistent in Libya. Livestreaming would have been prohibitively expensive, if not impossible. However Twitter worked well, and provided a low bandwidth opportunity to create a relationship between individuals inside Libya and those abroad. As bandwidth increased and the Libyans running Alive in Libya increasingly focused their efforts on video production, the #AskaLibyan hashtag was left behind.

I was recently approached by Jessica Christian, Communications Director for Circle of Health International, about livestreaming from the Zaatari refugee camp, on an upcoming delegation to support Syrian mothers. I was initially skeptical, and a quick google seemed to confirm connectivity is very weak in the camp. I asked her a bit about her goals with livestreaming, and primarily she wanted to connect their donors and supporters with the work they helped create. Secondarily, she wanted to reduce the amount of post-production work that remained after the trip.

Livestreaming could be a great way to solve this, however the primary gain from “live” necessitates real-time interaction. Livestreaming has been a growing trend in mobile and social storytelling. It exploded during the Occupy movement, but has been growing for a long time. It’s easy to understand the appeal of “live” due to the increasingly real-time nature of the internet. For Jessica and her colleagues in Jordan to engage in real-time with their supporters in Texas and elsewhere, she’d have to overcome a nine hour time gap. I suggested she consider the low connectivity in Jordan and the time gap an opportunity to try something different.

Using a unique hashtag she can create an asynchronous dialogue on Twitter that may also engage others outside of her network. Telling her story in short bites sorted with a hashtag creates a collaborative narrative that her donors and supporters participate in. Add to that Twitter’s new photo-first policy and you have an even greater opportunity. Although much vaunted, video isn’t everything. A series of great portraits, with 140-character quotes from the subjects can bring distant communities to life. Sharing them on twitter, with a replicable hashtag creates the opportunity for a collaborative narrative, and may bring you surprising new voices.

by Jonathan Pednault

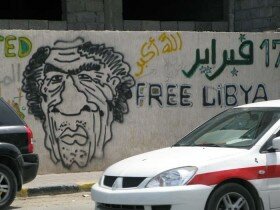

Squeezed between the sea and the walls of the old city, the Corinthia hotel once droned with swarms of squatting journalists and activists that anxiously awaited the capture of colonel Gaddafi, drinking pitch-dark Nescafés on tables coated with ashes and unwashed plates of half-eaten meals. Nowadays, the luxurious building has reverted to its old, regular clientele; businessmen, politicians and civil society moguls that quietly chat in the smoke-free lobby while drinking macchiatos. For some at least, life goes on in Tripoli. And for the journalist who remembers the city at the excitingly gullible peak of its post-liberation joy, the cold shower of unforgiving realism that has rained on Libya since two years now has one question the very notion of the freedom that was fought for.

Traveling as a journalist is poles apart from traveling as a journalist trainer. The questions, the energy and the mindsets are different. From researching the best ways to paint a given situation to teaching others to do so, one at times loses a sense of perspective of what exactly happens in the country to concentrate on the well-being and progression of the trainees. Political systems, social contexts and events become elements to deal with and experience rather than merely describe and analyze. In a place like Libya, no matter how short the stay, this means experiencing the doom and despair of the post-revolutionary state of affairs with and through the trainees instead of simply noticing it.

A hundred miles south of Tripoli stands the demolished city of Bani Walid, a former stronghold of Colonel Gaddafi. Amongst its rubbles lives one of our trainees, a short and nervous man from the Warfala tribe. Everyday, he’d make the two hours drive to the capital to attend the SWN workshop and undergo his university lectures. For him as for many others, the revolution, it seems, had not proved a great leap forward. With his house destroyed and his family less influential, he now had to keep silent his last name for fears of retribution from former rebels and revolutionaries, still keen on singling out families that had ties with the regime. He was, after all, but the distant nephew of some obscure Gaddafi official. Enough for a good beating by some katiba members, he feared. But his fear extended farther – except to the trainers, he would not tell his colleagues of his tribe’s name. Too afraid, he said.

Afraid: other trainees were too. Despite the powerful promise of free speech brought by the revolution, there remain some topics that in the eyes of many are best left unspoken and unseen. Such as the huge garbage dump that some thought wise to install right by the Mediterranean sea after the revolution. A coastal landfill site that one of SWN’s trainees – a tall and heavy black Libyan with little prior experience in journalistic production – found the guts to film, after much fear and much encouragement. And this, despite the place being the property of a family of former katiba members and friends of his, who were absolutely not keen on having him nose around. Venturing at dusk on the parcel of land, he came up the next morning with depressing images of trucks dumping tons of trash into the sea, garbage-burning fires and desolate landscapes.

An impressive piece of local journalistic work produced with StoryMaker, SWN’s trainee did what no foreign camera crew would have ever been able to emulate in such context. A strong testament, overall, to the StoryMaker application’s capacity to enable strong yet discrete production of multimedia content in a difficult media environment. In that regard, the StoryMaker training provided by SWN could hardly be more in touch with the realities faced by the many activists and journalists who operate in dictatorial or transitional political spaces such as Libya. Small and inconspicuous, the Androïd devices on which the application runs can easily be dissimulated. Easy to use and provided with a practical off-line curriculum, StoryMaker can be employed by anyone – with or with no prior shooting, editing or journalistic experience. Quite an advantage in places where users do not necessarily have a lot of existing computer or technical knowledge. And a cheap option for places where cellphones are already readily available and used.

Two years later, the revolution has brought little to the Libyans if economic uncertainty, political instability and social discouragement and fear. The transitional waltzes, cadenced with intermezzos of AK-47, car-bombs and political assassinations, haven’t quite yet lived up to the Libyans’ dreams of democracy, freedom and economic growth. Their critics nowadays barely stop short from longing for the good old days. And the ardor of the revolutionary spirit that engulfed the determined youth has now left place to the unchallenging dictatorship of the «Inch’Allah» mentality. The actors and factors are so many anyway that one would have trouble finding any defined entity to rebel against. And so life goes on, indeed. A depressing one, for that matter.

But where hope seems slight, the few that keep on striving for the greater good often carry the secret ambitions of the many. Journalism trainings of the likes that SWN recently carried on in Tripoli are but a drop of water in front of the ocean of unpredictable predicaments that surrounds Libya. But independent and well-trained media professionals equipped with the latest tools provided by technology can, in this age of social networking, change the self-perception of a people and the course of a nation. Surely more than macchiato-drinking businessmen, politicians and civil society moguls, anyway.

Jonathan Pednault is a freelance journalist from Montreal, Canada. In the spring of 2013, he was an instructor for a mobile phone multimedia production workshop in Tripoli, Libya, using StoryMaker. It was his first experience working with SWN.

This account of SWN’s workshop for Syrian media producers in partnership with IWPR was written by Mark Rendeiro, whose work can be seen at citizenreporter.org. A podcast featuring students from the workshop can be heard here.

This past April, Louis Abelman and myself went to Istanbul to give a video story telling workshop specifically for Syrian reporters living and working in conflict zones. The workshop was a project from the Institute for War and Peace Reporting and consisted of 5 days of class time, 4 of which were dedicated to video related details such as recording and editing. The class was made up of about 12 students who live in cities such as Aleppo, Deir-ez-Zor, and Idlib. They were, on average, in their early 20’s and all involved in either writing, photographing, or making video reports of war and life in their cities for mostly local online and offline media channels.

Probably the most eye opening detail about these participants was that hardly any of them had ever wanted to be reporters or journalists prior to the war. 2 years ago they were students at universities and technical institutions studying for non-media related careers. The outbreak of war was the catalyst that led them to this sense of personal responsibility to report for both Syrians and non-Syrians to inform them about what is happening where they live. And in these last two years they had seemingly had a crash course in journalism, learning along the way, while dealing with the tremendous risk and losses that this war has brought them.

During the course of this workshop where we taught camera shots, fundamentals of editing, and discussed what makes a story interesting or compelling. Students also showed us their previous work. It is a classic but frustrating moment to see examples of shaky and poor quality footage that was recorded at tremendous risk in what are hostile places where- had it been known they were filming, they could have been killed. While it is understood that having a clear and steady picture is much harder when you’re dodging bullets and hostile soldiers, it is almost an unworthy risk if the video you record is impossible to look at or understand. That is the difficult balance of being very dedicated to reporting but not being well trained to do the best possible job in those circumstances. Thankfully such workshops do exist and organizations like the IWPR make the effort to not only get young reporters to Istanbul but to find those who are already dedicated and doing what they can, to then take a few days and get further training.

The level of experience and ability of students from when you get them to when they head back out into the field can always vary, especially when you have reporters that have a lot more on their mind than just how to do an overlay a clip in Premiere. War trauma is a reality that very clearly plays a role in such a classroom, affecting how much people can learn and focus on any given day. Thankfully our Syrian students were across the board determined to learn and build upon what they know with each new project.

By the end of the week we had a few people who came out of the workshop capable of producing media that would interest and fit the quality standards of most 24 hour television news networks. We had more people who had advanced from individuals who had never edited video to now being able to shoot and edit their own complete stories. Many seemed to leave with a new outlook on what kind of stories would serve their purposes better, to shed light on the dire situation in their community.

It is a logistically and pedagogically challenging task to bring reporters out of a war zone temporarily, figure out what skills they have and what can be learned within a limited time frame, and then return them to their communities. It is also a very inspiring and humbling experience to teach skills, share experience, and in-turn learn from the talent and resolve that these young reporters showed us. Our hope now is that our efforts help them do better work, and that we can see them again, in a time of peace, in these beautiful places we have heard so much about.

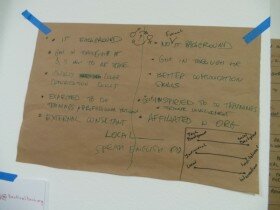

This week I’m in Berlin for an event organized by Tactical Tech, meeting with various trainers in the digital security space. The big question on the table is how to improve materials available to trainers. The bulk of materials in this space are written as informational material for end-users. If you want to increase the adoption of digital security practices, you have must also increase the capacity of individual trainers to teach these subjects.

Last year Small World News spent a number of months developing a curriculum for mobile journalism, including a section with 10 modules on mobile safety and security. Currently these lessons are written in a style for user-directed learning.

As part of the gathering here in Berlin, I’ll be working on making these modules more accessible to other trainers. To expand their relevance, I’ll have to take the existing content, and develop a teacher’s textbook. Teacher’s textbooks go beyond what a student has in front of them, to expand the learning with elements such as demonstrations, activities, and quizzes.

We hope to follow this event by disseminating the material to other trainers and supporting broader collaboration and resource sharing. We believe broad sharing of Creative Commons licensed material will increase the body of knowledge available to trainers and users alike.

The International Center for Journalists’ IJNet and Mashable recently recommended Brian Conley’s Tedx talk as one of “4 Ted Talks Worth Watching.” You can check out Brian’s talk below, and then see the others on Margaret Looney’s original article.

Citizen Journalism is Reshaping the World

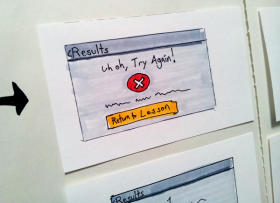

We are fast approaching the release date of our multimedia storytelling app. In recognition of this, Steve and I have been doing some field testing with local colleagues, to work out any last minute kinks and get an overall sense of the functionality and reliability of the framework we’ve prepared.

One of our primary angles is the idea that most stories are built on fairly standard, well used formulas, or templates. These templates are fairly standard across the international press, including Al Jazeera, and others. To ensure our formulas were flexible enough to fit a variety of contexts, we travelled to Tunisia to work with a small media center and netcafe based in Kasserine.

Additionally, we wanted to be sure the formulas were clear enough to provide an approachable framework for users with no prior experience in reporting or producing media. We spent four days working intensively with three Tunisians, and met with a number of others to learn more about the state of media and mobile use in southwestern Tunisia.

After producing just a few stories, and without any formal coaching, Rashed, who never produced media before, showed a noticeable improvement in the quality of his content.

Our other colleagues, Mohamed and Naim, have a bit more experience in media. Mohamed started an audio podcast and web radio program in 2007. Naim ran a blog critiquing the regime throughout Ben Ali’s days and was detained and beaten severely by the police during the revolution.

All three immediately recognized the potential impact of the app, and we are very much looking forward to what they will produce when the app is released in beta by the end of the year.

Do you have a story to tell? Have access to an android media device? If so, get in touch, we a actively seeking beta testers over the coming months, in the Middle East, the US, and elsewhere.

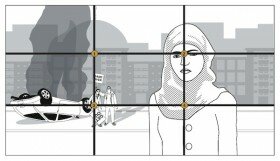

As part of our forthcoming multimedia storytelling app, we are working on simplifying video composition. One of the app’s primary features is to provide training to the users. Each user will be able to improve her multimedia production skills as she learns to use the app.

In order to ensure the app provides the greatest training impact possible, we have to work to ensure that it can teach users without the involvement of a human trainer. Small World News has generally made its mark by providing high quality multimedia and new media training to individuals in difficult to reach places. We recognize that in the future, if we are to expand, we have to create better tools for distance training, because we cannot be everywhere at once.

One of the most complex concepts to teach new students is composition, both what to put in the camera’s frame, and how to use different size frames to advance a story. Over the past week I’ve been reviewing dozens of random frames from a variety of movies and television shows.

I had a theory, going into the research, that there are clear rules that become clear after reviewing enough samples. Every first year film student learns about the basic shots: establishing shot, wide/long shot, medium shot, and close up. They also learn about the rule of thirds, a guide for using a grid pattern to help direct the framing of individual shots. The combination of standard shot sizes and a framework for composing the shots leads to a finite number of “standard shots.”

So far the research seems to back this theory. I have reviewed more than a dozen shots in each of 4 categories, chosen randomly via google images searches. I’ve found that there are slightly different guidelines for the size of the primary subject in each type of shot.

In an Establishing Shot, individual human subjects tend to fill less than 10% of the frame, and the foreground fills only the bottom third of the frame. The horizon and background fill at least the top two thirds.

In a Long Shot, human subjects fill between 15-20% more than 60% of the time. The total range tends to be between 15 and 30% of the total frame. The rest of the frame is filled by the immediate location where the scene takes place, and the horizon is often not visible.

In a Medium Shot, human subjects fill between 30% and 60% of the frame. The rest of the frame is filled with the area surrounding the subject, though specific details may not be distinguishable.

In a Close Up, human subjects fill between 40 and 70% of the frame. In a Close Up the subject’s location is indistinguishable.

As we get closer to finalizing the curriculum for the app, I’ll be researching additional rules and guidelines we can implement. I hope these revelations will assist other trainers, journalists, and citizen journalists to create more interesting compositions. Particularly for newcomers and amateurs to he medium, effective use of different types of shots can greatly increase the impact of still and video images.

Brian Conley

As Steve wrote last week, Small World News is developing a new mobile multimedia reporting app for Android. This app will also include an entire mobile multimedia reporting curriculum, including journalism and digital safety and security basics. We will be adapting our Guide to Safely Producing Media where appropriate and working with our colleagues John Smock and Mark Rendeiro to produce the photo and audio reporting lessons.

I have been tasked with producing the security curriculum for SWN’s new mobile app. Because of that, I’ve spent quite a bit of time the last few weeks reading a variety of existing digital security and safety guides.

How much security or privacy is “enough” tends to raise consistent and sometimes rancorous debates within the relatively small community of digital security & safety researchers and trainers. Combine this with the large number of safety and security guides currently available, and the lack of any central review mechanism and you start to have an idea why this has been a tough few weeks.

While reviewing the tools available, and what the guides say about them, I’ve come to realize there are potentially fatal flaws even in a few relatively well-regarded tools. The curriculum I’m working on is focused on mobile-based reporting, so most of the tools and techniques I’ve been reviewing are related to mobile, and all are related to digital/online communications.

My observations thus far are that the issues with training users to improve the security and safety of their communications generally fall into a couple of camps.

Security issues related to the “design” of a tool.

Recently I realized that TextSecure, the most well-regarded secure texting app for Android has a serious security hole, due to the application being designed for “usability.” TextSecure is a tool that saves your text messages in an encrypted form, and allows two users of the app to send encrypted messages to each other that are decrypted on the recipient devices.

To increase the usability of the app it has a feature described by one of the developers as “in focus.” Understandably, a user of TextSecure would not want the passphrase used to decrypt a message to stop functioning while the message is being read, and thus “in focus.” Unfortunately, as the app currently functions, if I lock my screen while reading a message, or while the list of all available messages are open, the passphrase cache does not clear based on the preset timeout.

This is a huge issue because it also means if an activist or journalist is in the middle of reading/reviewing/deleting texts and detained, the most natural action for a user is to enable the screen lock. In the case of TextSecure, you will have to quit the program before enabling the screen lock if you want to release your passphrase.

This is a case where a tool being designed for usability actually puts the user at risk, and the technique necessary to ensure safety is not intuitive and thus has low usability.

Although TextSecure is a tool designed for increasing a user’s privacy and security, the tendency for non-security tools and technologies is to prioritize usability above all else.

Security issues related to simplicity of the tool, or users’ clarity as to how it works.

The largest general threat to users safety is due to a lack of understanding about how a tool works. Sometimes a tool recommended by many may have a very simple flaw that may be overlooked by the user.

Truecrypt is a tool for encrypting hard drives that is relatively well accepted by the security community across the board. However Truecrypt has a fairly simple flaw, that technologists may generally be aware of, but is often overlooked in the training literature. According to Truecrypt’s site:

When a file-hosted TrueCrypt container is stored in a journaling file system (such as NTFS), a copy of the TrueCrypt container (or of its fragment) may remain in the free space on the host volume. This may have various security implications. For example, if you change the volume password/keyfile(s) and an adversary finds the old copy or fragment (the old header) of the TrueCrypt volume, he might use it to mount the volume using an old compromised password (and/or using compromised keyfiles that were necessary to mount the volume before the volume header was re-encrypted). Some journaling file systems also internally record file access times and other potentially sensitive information. If you needplausible deniability, you must not store file-hosted TrueCrypt containers in journaling file systems. To prevent possible security issues related to journaling file systems, do one the following:

• Use a partition/device-hosted TrueCrypt volume instead of file-hosted.

• Store the container in a non-journaling file system (for example, FAT32).

That’s a long way of saying, if you want to use TrueCrypt safely, you need to be sure to use a non-journaling file system for the drive where you wish to use TrueCrypt.

Until recently, I was not aware of this serious issue. The Protektor Services and FrontlineDefenders Digital Privacy manuals do not cover this issue, yet TrueCrypt is now considered a standard tool by most organizations doing training. I recently assisted a training on TrueCrypt, yet I was unaware of the flaw. This tells me, even if the issue was covered (I am fairly certain it was not) it wasn’t covered well enough that I, a relatively knowledgeable user, picked up on the issue.

When some of the most well accepted tools have serious flaws, and despite the existence of very simple solutions, these solutions are not made clear in the standard security training literature, we have a problem.

Security issues related to the usability/accessibility and actual functionality of tools to common users.

This is the elephant in the room. Users will not adopt tools that lack usability, no matter how high their need for security. This fact appears to have been key to the creation of Cryptocat, a relatively new security tool, which has recently been quite a bit in the media spotlight.

The problem with Cryptocat, as many have pointed out, is that usability may lead directly to broad user adoption, and users’ lack of understanding of how the technology works means they won’t be aware of the threats posed by Cryptocat.

Cryptocat aims to “Provide Universally Accessible Encrypted Instant Messaging.” Unfortunately, at the moment Cryptocat does this primarily through the use of SSL, which is far from a guaranteed measure of security. It also does not “anonymize you,” nor “protect against keylogggers” or “untrustworthy people.”

The good news is that Cryptocat seems to be providing a good lesson to the community. There has been a really engaging discussion on Stanford’s LiberationTech mailing list regarding the responsibilities of security researchers and trainers to the wider community of users. Nadim, the lead developer of Cryptocat, is taking on the difficult task of developing a cryptography project that is usable, clear to the user, and truly secure.

Lastly in the world of mobile security, individuals seem to be increasingly aware of the manifold risks posed by their phones and smartphones. However, there is one major flaw that is seldom discussed. This flaw is, essentially, the difficulty posed by the specific technology used to store data on smartphones. As my colleague Nathan Freitas put it recently:

Training orgs must ensure that they teach people “How to smash a smartphone into a thousand pieces using a heavy lamp and flush it down the toilet,” as standard curriculum.

Fortunately there’s another option for users of the latest Android OS phones: Full Disk Encryption. The implementation combines usability, clarity for the user, and high functionality. These factors all combine to ensure that Full Disk Encryption can and should be recommended as a standard practice for activists, journalists, and privacy advocates who have access to phones running Android 4.0.

I hope the curriculum we are producing will meet these requirements as well. Moving forward, I’ll focus on a simple test to determine to what degree a manual or tool provide for the safety of the user. Measuring the usability, clarity, and actual secure/private/anonymous functionality of a tool should determines the degree to which one should depend on it for safety.

Usability + Clarity + Functionality = Safety.

Small World News is excited to announce that we are designing a yet to be named android app. The app will support citizen journalists and professionals alike in the production of multimedia news packages.

Specifically, this open source app enables existing and aspiring journalists all over the world to produce and publish professional-grade news with their Android phone, as safely and securely as possible. It provides an interactive training guide, walkthroughs, and templates for users to follow as they plan their piece and capture media. The app then helps assemble the content into a finished format, with cuts and basic graphics.

Our long time colleagues at the Guardian Project will be handling the development work for the app. They’re one of the best android development organizations out there and we should know. We’ve been testing out their amazing suite of applications for a few years now.

Poor digital and mobile security are an increasing threat to journalists and their sources. Partnering with the Guardian Project, will enable us to produce an app that considers the needs of media producers and sources over the entire journalistic process.

Initially, this work is being sponsored by two organizations, Radio Free Asia and Free Press Unlimited.

Radio Free Asia is a private, nonprofit corporation that broadcasts news and information in nine native Asian languages to listeners who do not have access to full and free news media. The purpose of RFA is to provide a forum for a variety of opinions and voices from within these Asian countries.

Free Press Unlimited is a Dutch media development NGO active in over forty countries, focusing on strengthening the capacity of local media professionals and media organizations.

This app will help improve the quality of mobile reporting, while ensuring a more safe and secure model of connecting creators with their audience than currently exists. We’re thrilled to be envisioning what’s next for mobile journalism. We will be blogging our work as we complete different parts, and we’ll be inviting beta testers to get involved later in the fall. So follow along our blog if you’d like a chance to be included in the early tests.

Steve Wyshywaniuk

One week ago, today, two video journalists from the city of Misurata were kidnapped while covering Libya’s historic national elections. I had the pleasure to meet and work with these men during my recent trip there with my colleague and co-trainer Louis Abelman in May 2012.

Abdelqadr Fassouk and Yusuf Badi worked together as part of a three man team during our video boot camp in Misurata. Together they worked to produce a story about the head of the nursing department at Misurata’s only hospital.

The team did great visual work at the time, demonstrating a clear understanding of how to produce brief news packages. However they missed one small detail. They decided to record the video without audio.

When Louis and I explained their mistake, Abdelqadr and Yusuf insisted on reshooting the piece in its entirety. They exemplified a typical character of Misuratis, willingness to do whatever it took to get the job done.

Though the two men work well as a team, it’s clear sometimes they face some tension. Abdelqadr wished to learn the basics of editing. He wanted to finish the piece quickly and submit it to the election awareness campaign SWN was working on with the support of Doha Centre for Media Freedom. Yusuf, on the other hand, was far more interested in cutting and re-cutting the piece. His goal was not to finish the piece, but to understand the editing software, deleting the finished sequence and starting from scratch each time.

The term “Frenemies” might be fitting. Both men were generally good humored and if they aren’t getting in each other’s way, I trust they’d have no better companion in such a trying time.

Despite their good company, I am greatly concerned about their safety. The Facebook era has meant that repeated false claims of their release have been widely distributed by colleagues, friends, and fellow Libyans who desperately want the news to be true. As of this writing, Abdelqadr and Yusuf are still detained, and though their general whereabouts are believed to be inside Bani Walid, their specific location is unknown.

Misurata and Bani Walid have a longstanding feud, exacerbated by the Libyan revolution. The kidnapping of two much-loved journalists from Misurata has pushed the conflict again to the front of discourse about the future of the new Libyan state. So far, Facebook rumors notwithstanding, negotiations have not yet completely broken down. Though many are campaigning to use the kidnapping as a pretext to return to war, they’ve thus far not been successful. For the sake of Abdelqadr, Yusuf, and all of Libya, I hope our friends will be freed without further violence.

Brian Conley

Small World News

[For additional information about Abdelqadr Fassouk and Yusuf Badi, see the Committee to Protect Journalists’s Libya alerts, Reporters Without Borders, and articles by the Libya Herald, Associated Press, and McClatchy.]

The Misrata trainees have so far done justice to their town’s reputation as a hard-working, can-do kind of place, and are well on their way to fulfilling the mission we set out: to produce four videos in four days. They seemed to be satisfied with our second day spent covering production basics, as many of them have prior production experience (more on that below) but none have had formal training.

Most of the guys (they are all guys, unfortunately) picked up cameras during the fighting that ravaged their town last year and became the media arm of the uprising. Some worked as fixers for the international press. They are amateurs who have more experience filming in situations of intense stress than most professionals. But though they have proven their bravery and bonafides as war photographers and cameramen, displaying their trophies– I was shown several pictures of Qadaffi’s corpse with one of our proud trainees working a camera in the frame (pictured above)– they seem to have not quite figured out how they will transition to becoming peacetime media professionals.

In addition to their inexperience, we can add their youth and thirst for adrenaline as obstacles to professionalism. Maybe there is less glory in covering a local election than a firefight, so there’s a constant push to spice things up, to add special effects to any production. Dramatic music. Anything from After Effects: explosions, fire, wild text animation.

What kind of work will they produce? Will they take up the calling of journalism and its accompanying watchdog ethic, at least as we traditionally understand it in the west, or will they continue to produce propaganda for their “side”– their town and their Katibas [militias or brigades]– as they risked their lives to do during the revolution?

Our challenge is to temper some of their enthusiasm and show that there is satisfaction in assembling a documentary style story about real life. To that end we are pushing them to defy their own instincts and make something “boring,” maybe just to make us, the foreigners, happy. So far it’s working: all the trainees are making projects that conform to the vision we set out, showing disciplined and respectful attitudes toward what we are telling them to do (they take pride in having that kind of attitude here).

Misrata is not traditionally a media town, but the field is open for these young guys to build a professional media sector here, if they want it.

Tonight we’ve arrived in Misrata, the site of our next workshop. The city lies along the Mediterranean coast 187 km (116 miles) east of Tripoli and is Libya’s third largest, a commercial hub hit hard by the war. It’s been a year since revolutionaries cleared the city of Qadaffi loyalists after months of deadlocked fighting, and the blast marks of howitzers and machine gun fire still scar Tripoli street, the now infamous main drag. Misrata has a fiercely independent streak within Libya today, due to its unique role during the war and the contributions of its militias to Qadaffi’s final overthrow (it was in Misrata that the leader’s body was displayed to the public in a meat locker). Misrata’s name is also freighted with significance within the community of foreign reporters, as it was here that the distinguished photojournalists Tim Hetherington and Chris Hondros were killed.

There is some sense in Libya that Misrata is a world apart, a sort of city-state where residents started the work of building the post-Qadaffi order on an accelerated timetable. City council elections were successfully held here in February of this year, months ahead of June’s planned national assembly elections (the national assembly will select a committee to draft Libya’s constitution). Misrata already has three of its own TV channels. Its victorious brigades have not been fully disbanded. As in much of the rest of the country these armed groups fall under the merely nominal authority of the national defense ministry, and do pretty much as they please.

We were received warmly by our hosts from the local media council at a spacious TV station by the sea. It was already late, but more than half of our prospective trainees were there to greet us. Brian introduced us with a now established good cop-bad cop routine, and prodded everyone to not be outdone by the Tripoli workshop’s videos; we expect strong work here. The facilities are excellent and the young people we met, many of whom established themselves with front-line reporting during the uprising, seem eager. We are told we are the first foreign media trainers in the city.

Guiding the enthusiasm on display to contribute to an election awareness campaign that is nationwide may present a challenge, as Misrata is still mending and residents are keen to display the wounds of their war. We hope to appeal to a sense of national purpose that will transcend local pride, as the contest of regional loyalties happening in Libya right now is one of the biggest obstacles in rebuilding the nation.

Small World News just completed the first in a series of video boot camps around Libya. Our first location was the capital, Tripoli. Several trainees work for television stations and production companies, while some are freelancers. We covered the basics of civic journalism, visual storytelling, and video production.

First we asked the trainees to propose compelling characters, initially a fish cleaner, teacher, revolutionary commander, Libyan Army soldier, an Amazigh elder, and a girl just one month too young to vote. After this we began focusing on the visual question. How can we tell the story of each character with visual sequences?

This is one of the most difficult concepts to teach aspiring video producers. Each sequence is generally made of five basic shots. Often trainees hear this and assume it means that any video can be produced with ONLY five shots. Often this mistake leads to videos with very little b-roll or visuals. The concept is to create series of sequences, each made up of any number of the five basic shots. These sequences are then put together, under the direction of the interview, to show the story being told by the interview subject.

Each group had to decide how to tell their subject’s story with visual sequences. Subsequent discussions led some groups to abandon their initial idea. Other groups found that their subjects, who had been receptive initially, became hesitant when faced with a camera. Others simply refused to answer their phones. This was a good lesson for all of the trainees in the importance of flexible planning on deadline.

We began the training with 20 trainees, by the end of day 2 there were less than 12. Such attrition has often been the pattern in Libya. Trainees’ work habits and commitments may be less than stable at times. When the trainees went out to shoot their stories, there were just 4 groups, of between 2 and 3 each. These groups subsequently produced 6 stories in part, completing just 4 by the end of the workshop.

The only similarity between the trainees who completed their video was an utter determination to complete their task. The skill level and previous access to camera equipment varied wildly. Two of the three tv stations represented completed a video, while the other half of the videos were produced by freelancers. Moving forward we will endeavor to provide more assistance to the less experienced and less confident trainees.

By the end of the next three weeks, and four more workshops,we hope to continue to diversify the content produced by trainees. We hope to produce videos representing a broader array of Libyan citizens, including women and conservative Muslims for example.

On to Misrata for our second workshop.

Small World News is in Libya for the third time since the revolution began. Although the revolutionary edge of the nation’s enthusiasm may have subsided, the enthusiasm itself has not. Libyans are excited to build their country, and actively looking for partners to provide assistance and mentorship. This desire led directly to the creation of our new project, a series of production bootcamps around the country. Throughout May, Louis Abelman and Brian Conley, along with Alive in Libya’s Mohamed M Essul will run a series of workshops across Libya.

We are excited by the broad support we have received from the Doha Centre for Media Freedom. With their support Small World News has developed a program that looks beyond training. We are using the phrase “production bootcamp” because we see each event as more than “training.” Our goal is to work side-by-side with Libyans across the country to produce a series of videos. These videos will form a campaign over the next several weeks encouraging Libyans to vote.

There is a general lack of capacity in the Libyan media to produce short, dynamic news packages quickly. Libyan news currently focuses primarily on talk shows, and studio-based news programming. By encouraging a bootcamp, on-the-job style experience, trainees will learn theory that is quickly informed by practice.

Currently there is also a huge lack of real information about the election. The day before registration began on May 1, many Libyans did not even know where to register. Others were confused about the exact purpose of registration. Furthermore, many Libyans are even unclear about when the elections should occur. Its June 19th according to our latest information, yet many still believe it is June 23rd.

The workshops will bring together a diverse group of media makers in each city. These trainees will work together in a series of production teams, conceiving a story, shooting the story, and finally assembling, all in a matter of days. We have crafted the campaign around the idea that individual Libyans are best suited to convince their fellow citizens to vote. We are attempting to blend short documentary features, telling one individual story, with energetic, get-out-the-vote style language. We hope this innovative approach will connect with average Libyans and educate them about the upcoming election.

Our partners and colleagues over at the Engine Room are dedicated to organizing the best practices and experiences in the world of tech development. Taking what they find and openly sharing it for all of our benefit. This is why it’s important for all of us to take their social tech census.

By pooling our knowledge together we can all benefit by seeing what has worked for us in different locations, and help avoid making the same mistakes over and over. It’s important that we take the time to step back and communicate with our peers on the work we’re all dedicated to.

Here at Small World News we’re looking forward to seeing the results, so be sure to add your voice to the census today.

The shaky footage and highly zoomed images of smoke, helicopters and gunfire have become hallmarks of visual reporting on events in Syria. With the increasing risks and mounting death toll of foreign journalists, citizen journalists have become an increasingly necessary source of information from Syria.

The increasing carnage has also led to an increasing insistence that more technology is the answer. Whether we are talking about drones, more drones, internet access, satellite imagery, or curating Syrian images, the discussion revolves around increasing the distribution of images and information from Syria.

I would like to propose an alternative perspective. I think the accessibility of images of carnage, awareness of the toll of violence and the assaults by Syrian security forces against civilians are currently sufficient. The issue is not the lack of images, the issue is the lack of stories. If narratives are not being crafted by the Syrians themselves, they will need to be crafted by those reporting on them. This is a dynamic that dramatically limits understanding, despite the broad spread of awareness.

Take for example this video shot in Syria earlier this year:

Assault in Homs

It’s great that the shooter recites the location and date of the video, at least it provides some level of context as to when and where it happened, but there is nothing telling the for more important details of how or why.

Now let’s compare it with a similar video from Alive in Baghdad in 2006, just a year after YouTube was launched:

Aftermath in Baghdad

I understand some may be inclined to say, “But the Alive in Baghdad team were trained and experience journalists, you cannot compare their work with Syrian citizen journalists and activists.” In that case, let me suggest this video from Alive in Libya, shot last summer, that depicts a similar situation:

Aftermath in Benghazi

Fortunately there are already some Syrians who have recognized the need to do more than document atrocities. Ahmed Khalaf, a British Syrian, has been producing some compelling work from northern Syria over the last week.

Aftermath in Idlib

I hope his work will increase awareness that training in visual storytelling and an emphasis on developing sympathy and understanding of the issues facing Syrians are far more important currently than a focus primarily on increasing the volume and visibility of more common user-generated content. Unless Syrians take responsibility to tell their own stories, and trainers and journalists outside encourage this development, I fear we won’t likely see a change in the status quo. We will continue to lament the plight of Syrians, while lacking any real context for how to help them, or any real awareness of the freedom they dream of attaining.

A confluence of recent events are highlighting an overlooked issue in Information Communications Technology (ICT) security. The most well-publicized event was the killing of Marie Colvin and Remi Ochlik in Homs, Syria last month. Until recently, it seems that online security has always been the province of “geeks.” Organizations whether news outlets, corporations, or activists and advocacy groups have relied on employing IT experts to manage and maintain their firewalls, properly defend against SPAM and DDOS attacks, etc. This is no longer acceptable. Journalists, activists, human rights defenders need to start watching their own backs, and they need better tools to educate themselves.

Traditionally, organizations rarely expected that each individual should take responsibility for her own security. It’s not only the lack of personal responsibility, but also the accessibility of educational materials that is to blame. As Danny O’brien at the Committee to Protect journalists noted last month, high-tech security information needs better dissemination. Individuals working in hostile environments are largely aware of the need to recognize analog threats to security, such as kidnapping or getting shot. Its time to begin taking responsibility to educate yourself about digital security threats. Furthermore, it is increasingly important for journalists to educate themselves about the security threats to their sources or they may become complicit in reprisals against these sources.

Journalists and their sources aren’t the only ones who need to be mindful of how their online habits put them at risk. Activists all over the world are increasingly leveraging ICT. The growing reliance on ICT and lack of proper “digital hygiene” increasingly puts them at risk. The Tibet Action Institute is a project that has been working on increasing the digital hygiene of Tibetan activists, since 2009. They have focused on raising awareness among Tibetans about the risks of sharing information with social networks, opening attachments from people they don’t know, and ensuring they utilize effective passwords and SSL connections. You might expect Tibetans would have the *most* understanding of their risk, due their independence and free expression threatened by the Chinese government for more than 50 years. In my own experience training activists connected to the Tibetan struggle, many are just as likely to follow poor practices. Because of this organizations like the Tibet Action Institute are very necessary, not only for Tibetans, but for activists, journalists, and average citizens all over the world.

If you had any doubts that being careful about your online habits only applies to Tibetans and others living in authoritarian regimes, look no further than Wired’s article about the new NSA Center. “Sitting in a restaurant not far from NSA headquarters, the place where he spent nearly 40 years of his life, Binney held his thumb and forefinger close together. “We are, like, that far from a turnkey totalitarian state,” he says.”

Small World News trains journalists, activists, and human rights defenders around the world, and what we consistently find is that individuals far too often fail to commit to good digital hygiene. I consistently find myself reminding even small groups of activists, you are only as safe as your weakest link. As we learn more and more about the extreme insecurity of technology we have come to depend upon, such as satellite phones, it becomes all the more important to provide the best manuals and advice to ensure best practices. This is why we released a guide to satphone security that is a follow-up to our previous guide to creating effective, high quality visual media more safely, and we expect these will be part of an evolving curriculum, our little bit of help to educate journalists, activists, and human rights defenders alike.

It was in this vein that I recently traveled to South by Southwest in Austin to participate in a panel called “How Not to Die: Using Tech in a Dictatorship,” (listen to the audio here) and will be speaking on a similar subject at a forthcoming Techchange seminar, New Media Tactics for Democratic Change.

If you’ll be attending the Online News Association and think increasing the dialogue about these topics is important, please vote for my session with Martyn Williams, “Basic online security for journalists – and why it matters,” and consider attending.

If you’re still not convinced our failure as individuals to take responsibility for ourselves is unacceptable, ask Marie Colvin and Remi Ochlik, these two anonymous Mexican twitter users, or finally, Maria Elizabeth Macîas Castro.

The recent hype and controversy around Invisible Children, and this post by Sam Gregory of Witness has encouraged me to expand on my initial thoughts seen here on Cartoon Movement. I hope this post can provide a bit of background on how Small World News came to its current incarnation, providing all manner of training and innovative support to journalists, activists, and citizen journalists, primarily in conflict areas.

It’s little known to those who first learned about Small World News in 2011, but Alive in was not chosen just as a catchphrase, but a core value. I first traveled to Iraq not to tell Iraqis stories *for* them, but to do my best to act as a window for the world onto the stories of Iraqis. While the traditional broadcast media reported to the world “Live from Baghdad,” I wanted to make the point that there were plenty of individuals capable to report “Alive in Baghdad.” I feel it is far more important to assist these individuals, individuals who were neither voiceless, nor invisible, but primarily unheard and unseen, to be heard and be seen, telling their own stories.

I will not disagree with Invisible Children on the point that images which reflect our own experience are easier to identify with. But this also means you are making a choice not to challenge your audience to consider different characters or voices equally valuable to the images traditionally seen on television. I didn’t start Alive in Baghdad and Small World News only to advocate for people in conflict areas and underdeveloped countries. Small World News was started out of a genuine desire to make the world smaller, by enabling citizens most affected by conflict to tell their own stories. I will not be satisfied just enabling them to tell their stories to Americans and first world citizens, i want to ensure they are able to tell them to each other.

Alive in does not seek to advocate for one policy or position. Small World News started Alive in to advocate for the presence of citizens in the stories told about them. Alive in suggests that no matter how good the journalist or the storyteller, it is no longer acceptable to only have stories told about people. Visual journalism and video advocacy is too often something done by experts and “humanitarians” to people or for people, not by people and with them.

Small World News exists on the notion that we want to change the course of media for the better. We want to ensure the existence of high quality, nuanced journalism into the 22nd century. The only way to do this is to ensure that those closest to the story have as much capacity and opportunity to tell their own story as the renowned, award-winning journalists currently telling their story to the world.

Since launching in March, our journalists operating in Ajdabiya, Benghazi, and Misrata have produced 175 videos covering the revolution, the civil war, and the daily life of Libyan citizens. With the fall of the Gaddafi regime in Tripoli, Alive in Libya has now expanded to the capital, along with a new bureau in Zintan.

Training in Tripoli

Last weekend Alive in Libya, led by our Benghazi bureau chief Seraj Elalem, completed its first training session in Tripoli. 10 aspiring journalists, 5 women and 5 men, graduated from our course, and 4 of them signed on as contributors to Alive in Libya. More trainings will follow in the coming weeks as we continue to expand into previously inaccessible areas. You can see a selection of the new content from our Tripoli bureau by visiting the website.

New Site

The first thing you’ll notice when visiting the site is the new design. We’ve revamped the look and feel of the website to better complement the tremendous video content coming out of Libya. We’re interested in your feedback on the site, so please let us know what you think.

The next thing you’ll notice is the stark improvement in the skills of our reporters. As the trainings continue and our reporters gain experience and grow more comfortable, they push the boundaries of Libya’s new free press. We are encouraging our bureaus to innovate, and they have responded with useful techniques like English narration (which their Western audience surely appreciates) as well as more probing and critical reports in the wake of the revolution.

Support the Team

Alive in Libya still needs your help.

Our team is currently expanding into other cities in Libya, and your support will allow them to both train more journalists and ensure these journalists are properly equipped with cameras, microphones, and other tools. Your support will be instrumental in the establishment and future success of new Alive in Libya bureaus.

If you can help, please click here to support our team.

Yesterday my colleague Steve Wyshywaniuk addressed how Citizen Media might assist Egyptians and the international community to bear witness to the upcoming election in Egypt. If the current ban preventing international observers continues, Egyptian citizens will be the only ones with the potential to ensure the validity of the election. After thirty years under Hosni Mubarak, and a sum total of 57 years of totalitarian rule, Egyptians can hardly be expected to ensure a transparent, accurate election.

Despite these limitations, its certainly possible Egyptians can follow the example of other organizations attempting to ensure democratic elections through citizen observation, from Lebanon to Afghanistan, and as Josh Mull mentioned earlier this week, they already have some experience.

I founded Small World News with Steve Wyshywaniuk based on the assumption that, while technology is increasing the accessibility of the tools of democracy, that access is so far primarily limited to developed nations and the wealthiest citizens of lesser developed nations. There are simple tools such as OpenDataKit to create mobile-based election monitoring forms, or even more simply, using simple SMS forms to rapidly send in election updates from monitors in the field.

However, these tools and techniques are only accessible where they are known to local citizens and monitoring organizations. Other tools, such as digital cameras that are now so affordable as to be practically disposable still cost a large percentage of a citizens income in Egypt or many other countries. Even where affordable cameras exist, too often citizen journalists lack the knowledge of basic production techniques to improve the impact of their firsthand access to urgent events.

-Brian Conley, Co-Founder

//photo by Al-Ahram

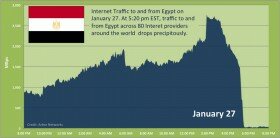

At SWN HQ we’ve been discussing creative ways Egypt might be able to ensure their upcoming elections are free and fair. At this point the love affair between the Egyptian people and the Web last spring is painstakingly documented. But the recent announcement that the military council will maintain the emergency law into next year, shows that they need to commit to a long term relationship. The rumored dates for the upcoming election are November 21st, which would mean this critical election would take place under the same atmosphere as they did under Mubarak.

Citizen media was crucial to kicking off Egypt’s revolution, and it will be essential for monitoring each step it takes. Election monitoring technology is available that can allow citizens to collect reports about problems via SMS, media will need to be more sophisticated, and information will need to be more clearly sourced.

Just as I hope the media campaigns step up in quality, it is likely that the reaction to citizens uploading video, posting tweets, and communicating over facebook will be more sophisticated too. Just as Libya has learned from Egypt, Egypt will learn from everything in the last year.

Written by: Steve Wyshywaniuk ~ Co-Founder

//photo credit: Patrick Baz/AFP/Getty Images

Yesterday in this space we discussed the upcoming elections in Egypt, and the need for international observers to work alongside local organizations to ensure the fairness and accuracy of the polls. International and local observers working together would allow reports of fraud, intimidation, and other improprieties to be more easily verified, increasing the legitimacy of the observation mission.

But what if Egypt’s military continues with its ban on foreign observers, and the burden of monitoring these critical and momentous elections is placed entirely on Egyptian citizens? What are some of the ways the observation mission can be empowered and bolstered without the presence of international monitors?

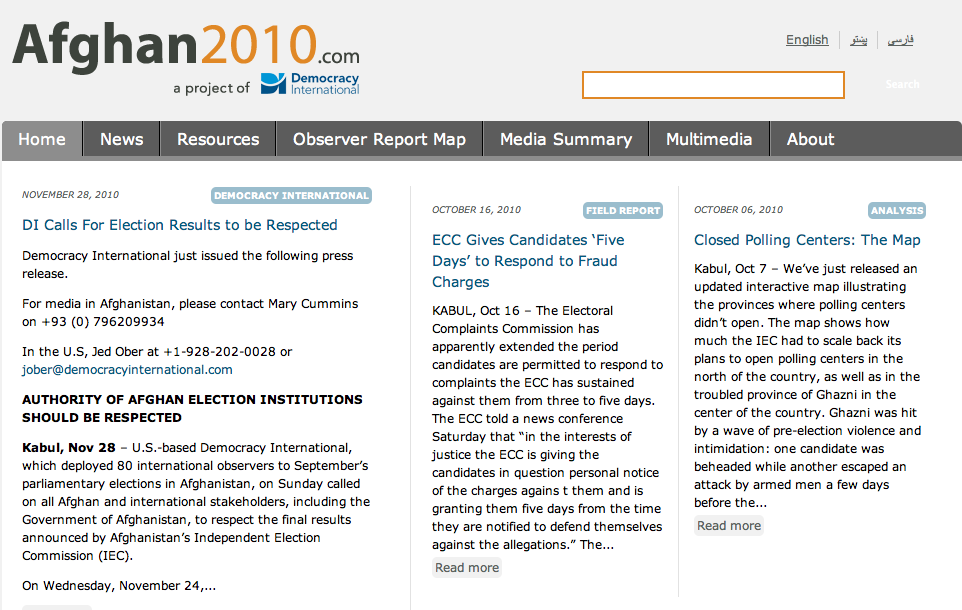

There are several examples of where election monitoring can be conducted in less than ideal circumstances, be it in police states with no access to foreign observers or in conflict zones with very little infrastructure and media access. Here are a few:

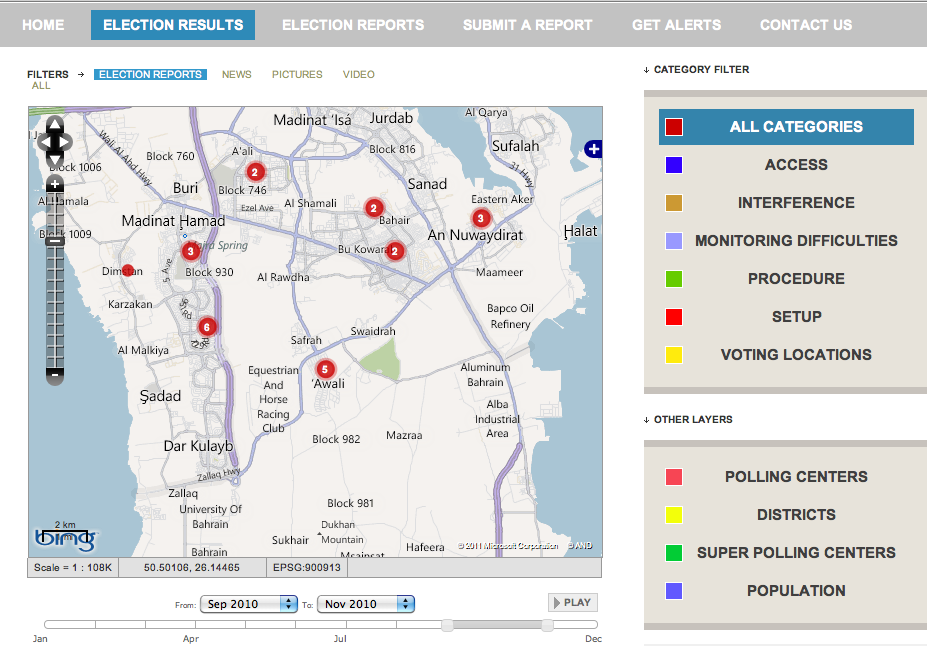

Afghan2010

Map Muraqeb

FEFA 2010

Monitoring elections is an incredibly complex and difficult task, particularly in this case with the crucial and unprecedented post-revolutionary elections in Egypt.

What are some of the other ways both the international community and Egyptian citizens can work to ensure a free and fair election? We will continue to monitor this story closely, and your suggestions, comments, and solutions are welcomed.

//Photo by Bikyamasr.com

Reuters reports:

Egypt will start parliamentary elections on November 21, Al Arabiya Television and the Al-Ahram newspaper reported on Saturday, the country’s first vote since a popular uprising toppled President Hosni Mubarak in February after 30 years of autocratic rule.

Al-Ahram quoted Egypt’s election commission head, Abdel Moez Ibrahim, as saying voting for the lower house, the People’s Assembly, will be held in three stages starting on November 21 and ending on January 3. Voting for the upper house, the Shura Council, will begin on January 22, 2012 and finish on March 4.

These dates aren’t confirmed, they’re only leaks to regional media outlets. A spokesmen for the military says only that the official dates will be announced on September 26.

The legitimacy of these polls, with history as a guide, are to be rightfully questioned. Reuters reports that some efforts are being made to ensure a free and fair election:

The [Supreme Council of the Armed Forces] has said the judiciary will oversee the vote to ensure a free and fair poll. A member of the council said in July the election will be held in three stages to make it easier for monitors to oversee voting.

One question is the role that international media and election monitoring organizations will play in the transition to credible democracy. Although Egypt’s revolution was successful in overthrowing the Mubarak regime, Egyptians still live under a military government accustomed to total domination of society, including within the judiciary offered as one of the primary election monitors.

In July, the military announced that there would be no foreign observers allowed to monitor the upcoming elections, citing the need to protect Egypt’s sovereignty. During Egypt’s last elections (under the Mubarak regime), fraud and election improprieties were widespread and well-documented by organizations such as DISC. For example:

Another report submitted on December 5, 2010 was even more specific: “Buying out votes in Al Manshiaya Province as following: 7:30[am] price of voter was 100 pound […]. At 12[pm] the price of voter was 250 pound, at 3 pm the price was 200 pound, at 5 pm the price was 300 pound for half an hour, and at 6 pm the price was 30 pound.” Another report revealed “bribe-fixing” by noting that votes ranged from 100-150 Pounds as a result of a “coalition between delegates to reduce the price in Ghirbal, Alexandria.” […]

Additional incidents mapped on the Ushahidi platform included reports of deliberate power cuts to prevent people from voting. As a result, one voter complained in “Al Saaida Zaniab election center: we could not find my name in voters lists, despite I voted in the same committee. Nobody helped to find my name on list because the electricity cut out.” […]

Reports also documented harassment and violence by thugs, often against Muslim Brotherhood candidates, the use of Quran verses in election speeches and the use of mini buses at polling centers to bus in people from the National Party. […]

As thoroughly and specifically as these incidents are documented, their validity may still be questioned due to the fact that they come singularly from Egyptian activists. Activists are burdened with incentives and interests that might tarnish the quality of their reporting. International monitoring organizations (such as the Carter Center or Democracy International) have their own disadvantages, such as questionable funding sources, motivations, and lack of local context. But when local and international monitors are used in tandem, incident reports can more easily be verified, and the credibility of the entire observation mission increases.

Somali refugees in Kenya lack basic access to communication and information about the aid and services available to them. From Internews:

The assessment surveyed over 600 refugees and shows that large numbers of displaced Somalis don’t have the information they need to access basic aid: More than 70 percent of newly-arrived refugees say they lack information on how to register for aid and similar numbers say they need information on how to locate missing family members. High figures are also recorded for lack of information on how to access health care how to access shelter, how to communicate with family outside the camps and more.

The report suggests a number of excellent solutions:

The report makes several recommendations, including: conducting workshops on communications for humanitarian organizations; establishing a humanitarian communications officer in Dadaab for communicating with affected populations; increasing support to Star FM, the main Kenyan broadcaster in Somali language, for broadcasting local humanitarian information; and establishing a communications research hub and a media training center for both host and refugee communities. It is important to note that the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) has already set up an Information Dissemination Group to specifically look into the communications needs of local communities “in the light of the current emergency and identified gaps by Internews’ assessment†(page 11).

What are some of the other ways that communication and access to information can be increased within the Dadaab camps?

Generally when media makers theorize on hyperlocal content, they consider it only in the context of developed communities with ready access to communication infrastructure (internet, television, etc). Further it is usually considered only as a complement to wider-scope media (such as the pairing of local news with nightly national news in the United States).

But the camp in Dadaab provides an especially difficult case, with its lack of access to most IT infrastructure (meaning no Facebook, no crowdmapping), and its need for exclusively local content (no need for international media organizations). The solutions that might immediately come to mind are almost certainly unworkable here.

Instead what is required is a concentrated effort on building the capacity of locals inside the camp to communicate and access information themselves. With this in mind, we can judge the recommendations of Internews’ report to be very much on the right track.